[본 글은 Immuno-modulating properties of Tulathromycin in porcine monocyte-derived macrophages infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. D. Desmonts de Lamache. 2019. 논문의 요약입니다.]

가을이 되면 육성비육농장에서 호흡기 질환을 동반하는 급성 폐사 증상이 발생하여 수의사 방문이 요청되는 경우가 많다.

대부분의 경우가 PRRS 양성 농장이었고 흉막폐렴균(Actinobacillus pleuropneumonia) 등과 같은 2차 세균감염과 건조한 날씨, 큰 일교차, 샛바람 등의 환경적 스트레스에 의해서 심각한 급성 증상이 나타나게 된다.

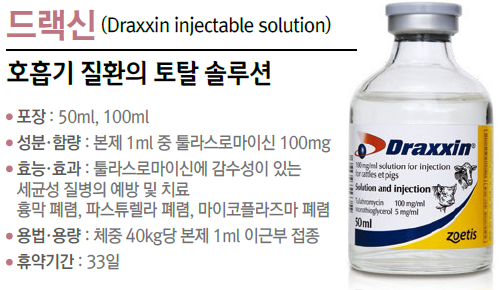

보통 응급적으로 전 돈군에 항생제 주사를 하게 되는데 대부분의 경우에서는 좋은 효과를 보지 못하는 경우가 많아서 농장주가 만족하지 못하는 경우가 많았다. 다만 증상 발견 즉시 드랙신(마크로라이드 계열 툴라쓰로마이신 항생제)을 전 돈군에 주사 시 만족할 만한 방어 효과를 보였다. 그래서 이러한 경험을 한 농장주들은 드랙신 주사를 일차적으로 선택하는 경우를 자주 볼 수 있었다.

일반적으로 드랙신은 문제가 발생하는 구간에 예방적 또는 증상 발견 즉시 사용하였을 때 장기간 호흡기 질병을 효과적으로 방어하는 결과를 얻을 수 있다. 하지만 그 외의 또 어떠한 특성이 있어서 PRRS 양성 농장에서 호흡기질병 방어에 탁월한 효과를 보이는지에 대해 생각해 볼 수 있는 최근 연구 논문이 있어서 공유하려고 한다.

미국에서만 연간 약 6,700억 이상의 손실을 가져오는 '돼지생식기호흡기증후군(PRRS)'은 양돈산업에서 치명적인 질병이다.[1] 이 바이러스는 폐포 대식세포(AM)[2, 3]와 혈관내 및 림파절 대식세포[2, 4, 5]와 같은 단핵구 대식세포를 감염시킬 수 있다. 이러한 세포는 면역감시, 병원체 사멸 및 적응 면역반응 자극에 중요한 역할을 한다.[6]

PRRSV는 대식세포의 식세포 및 살균 기능을 손상시키고 숙주 세포 사멸을 유도하여 종종 염증 반응을 일으키며, 아마도 가장 중요한 것은 돼지가 2차 감염에 걸리기 쉽게 된다.[7-11]

실제로 바이러스성(돼지 인플루엔자 바이러스, 오제츠키 바이러스) 또는 세균성(Streptococcus suis, Bordetella brochiseptica) 인자들은 기회감염성 병원체로 PRRSV 유발 폐렴을 일으킨다.[9] 이러한 시너지 효과는 자가 지속성 염증 반응을 촉진하여 질병의 심각도와 지속시간을 증가시킨다.[12-16]

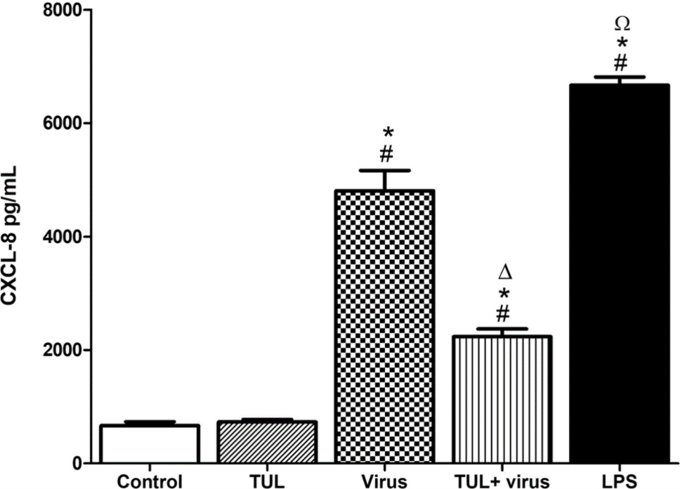

전통적으로 항생제 효능은 항균 특성에 따라서만 평가된다. 그러나 일부 마크로라이드계 항생제는 ROS와 CXCL-8 및 IL-6과 같은 전염증성 사이토카인을 조절하고 염증을 조절하는 지질 매개체의 생성을 변경하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.[17-22]

마크로라이드계 항생제의 직접적인 항바이러스 특성을 뒷받침하는 증거는 거의 없지만, 백혈구에 미치는 영향은 PRRSV와 같은 바이러스 감염의 맥락에서 유익할 수 있다는 가설을 뒷받침한다.[19, 20]

드랙신(TUL)은 PRRSV에 감염된 돼지에서 흔히 발견되는 그람 음성균인 흉막폐렴균과 관련된 돼지 호흡기 질환의 치료 및 예방에 사용된다.[9]

흉막폐렴균은 대식세포와 호중구에서 세포 독성 효과를 발휘하고 염증성 IL-6, CXCL-8(Interleukin-8이라고도 함) 및 류코트리엔 B4의 생성을 증가시켜 궁극적으로 심각한 폐조직 손상 및 사망을 초래한다.[23–27]

최근 연구에 따르면 드랙신(TUL)은 항균 효과 외에도 자극된 호중구와 대식세포에서 염증반응을 일으키는 인자인 CXCL-8 및 LTB4 생성을 억제한다.[21, 25, 28] 또한, 드랙신(TUL)은 호중구의 세포 사멸과 대식세포에 의한 식세포 제거(efferocytosis로 알려진 현상)를 촉진하는데, 이 두가지 모두 염증 해소에 중요한 과정이다.[21, 25, 28–30]

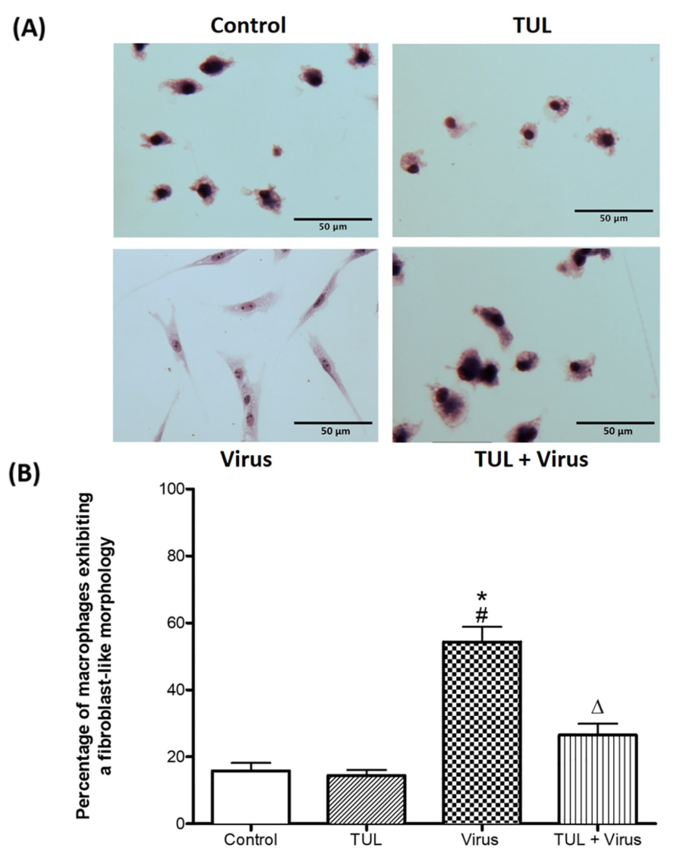

우리는 드랙신이 PRRSV에 감염된 단핵구 유래 대식세포에서 면역 조절 효과를 볼 수 있다는 가설을 세웠다. 이것은 직접적인 항바이러스 효과가 없는 드랙신(TUL)이 식세포 기능을 회복시킬 수 있고 PRRSV에 감염된 돼지의 단핵구 유래 대식세포의 염증 반응을 약화시킨다는 것이다.

15-60kg의 돼지에서 혈액을 채취하여 단핵구 분리하여 7일 동안 '단핵구 유래 대식세포(MDM)'로 분화시킨 뒤 드랙신을 실제 권장 치료 농도와 같은 상황으로 배양 배지에 넣어주어 실험을 진행했다.

실험군에 PRRS 감염은 북미형 바이러스 NVSL 98–7895주를 사용하여 2~24시간 동안 이루어지게 하여 관찰하였다. 형광현미경법으로 사진을 찍고 사이토카인 정량화를 통해 결과를 확인하였다.

요약 결론

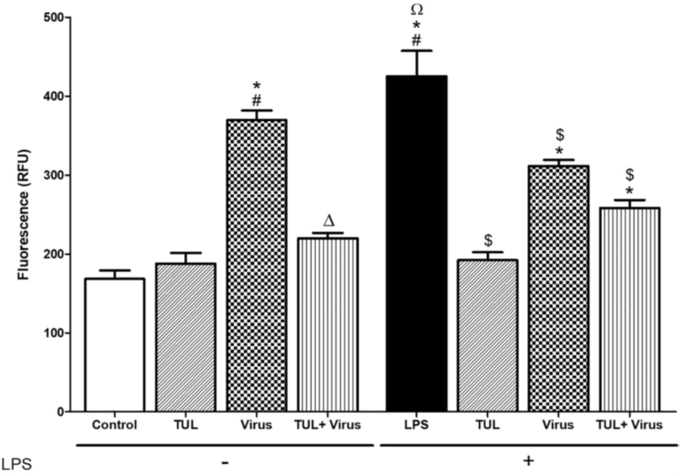

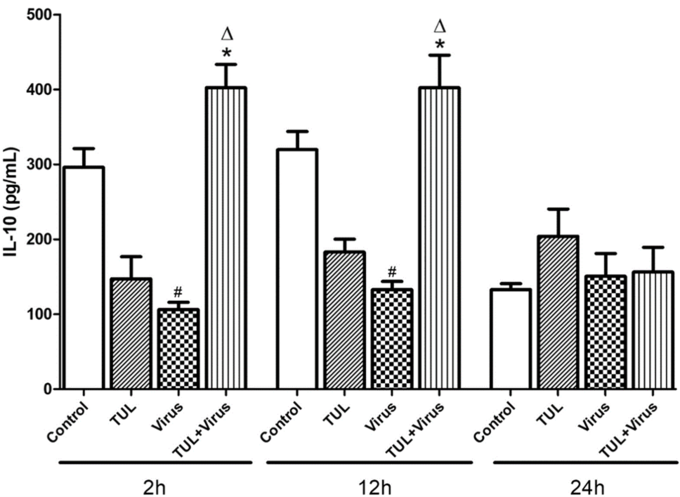

1. 드랙신(TUL)은 PRRS바이러스로 유도된 대식세포의 염증반응 신호(CXCL-8, ROS)를 줄여주고, 바이러스로 인한 IL-10(염증반응 억제 기능)의 감소를 막아준다.

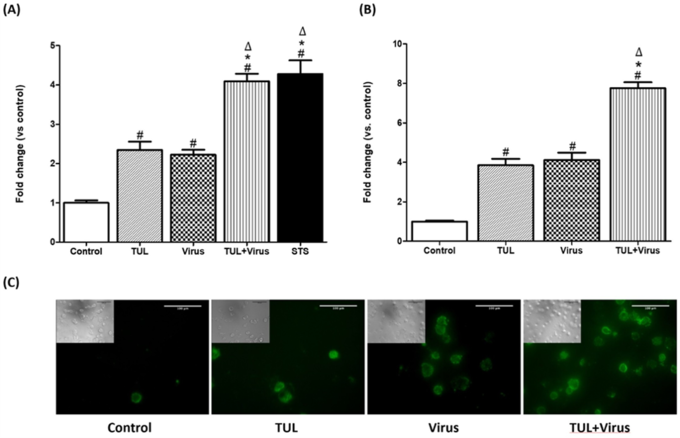

2. 드랙신(TUL)은 PRRS 바이러스 감염시 유도되는 괴사를 막아주고, PRRS 바이러스와 부가적으로 세포 사멸을 유도한다.

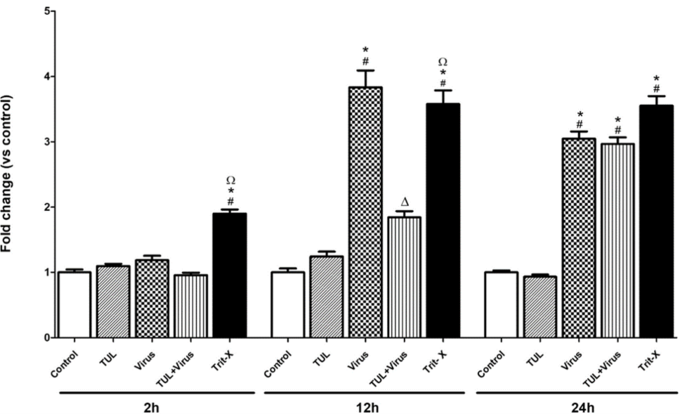

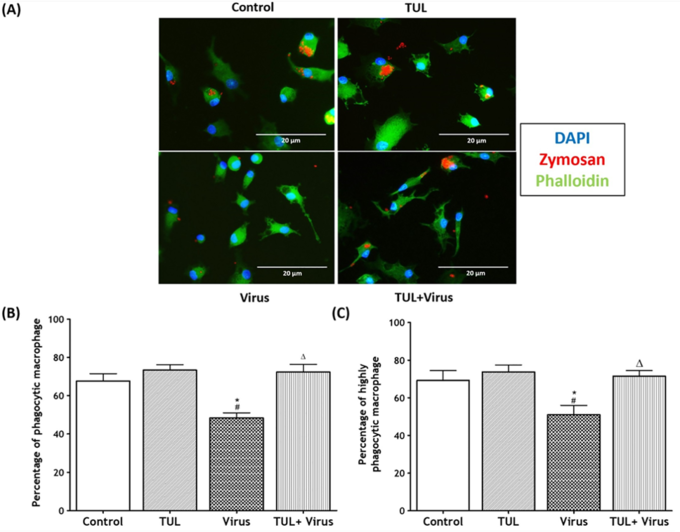

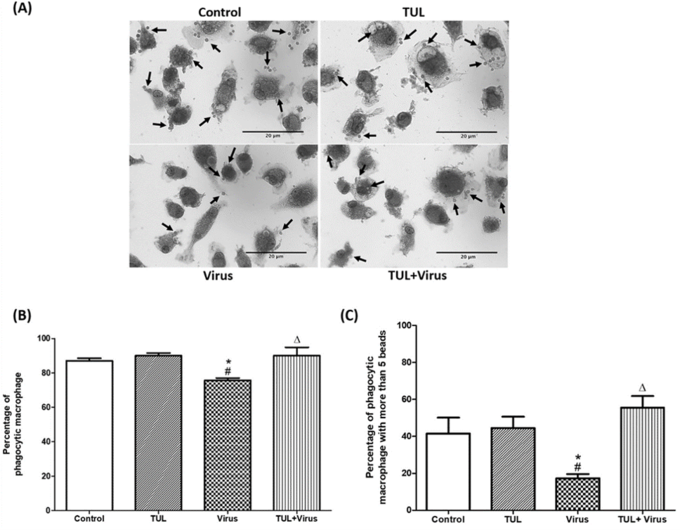

3. PRRS 바이러스로 인한 식균작용(비옵소닌과 옵소닌) 기능 억제를 막아준다.

드랙신(TUL)은 염증반응을 포함한 PRRS바이러스에 감염된 대식세포의 면역저하 기능을 억제한다.

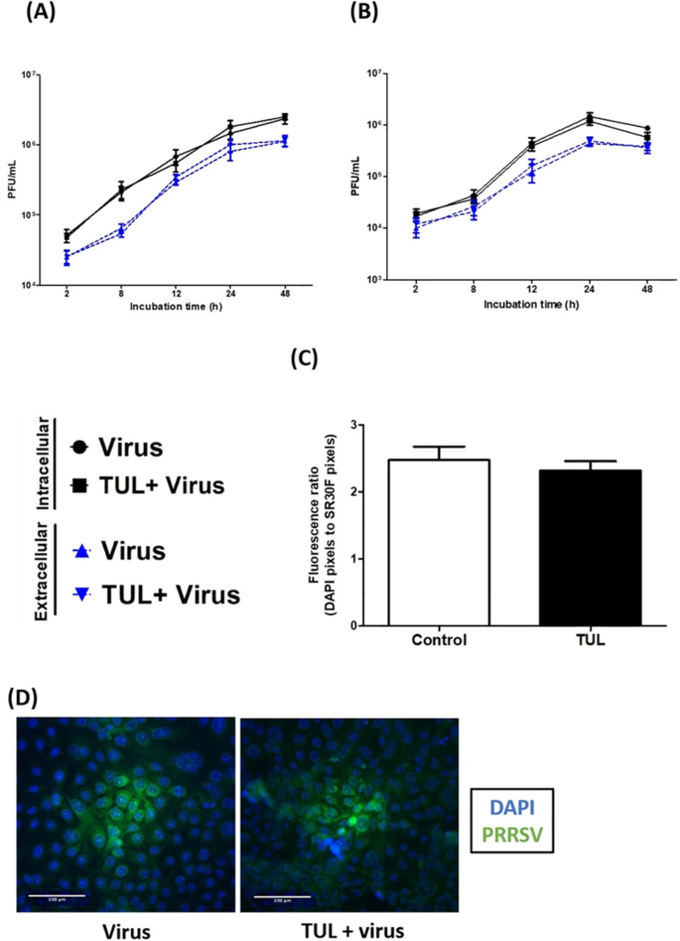

드랙신(TUL)은 세포 내 또는 세포 외 바이러스 역가를 변경하지 않았고 돼지 대식세포에서 바이러스 수용체(CD163 및 CD169) 발현을 변경하지 않았다. 다시 말해서 드랙신은 PRRSV에 대한 직접적인 항바이러스 효과가 없음에도 강력한 면역 조절 특성을 보였다.

드랙신은 PRRSV와 함께 대식세포 apoptosis(사멸) 유도에 부가적인 효과를 보였으며 바이러스 유발 괴사를 억제했다. 드랙신은 PRRSV로 유도된 대식세포의 염증 유발 신호(CXCL-8 및 미토콘드리아 ROS 생성)를 유의하게 약화시켰고, 비옵소닌 및 옵소닌 식세포 기능의 PRRSV 억제를 방지했다.

종합해볼 때 이러한 데이터는 드랙신이 돼지 대식세포에서 PRRSV 유발 염증 반응을 억제하고 바이러스로 인한 식균작용 손상으로부터 보호한다는 것을 보여준다.

이러한 결과가 추가적으로 실제 동물에서의 실험과 유럽형 바이러스를 통한 실험에서도 재현되는지 연구가 필요하다. 더 자세한 내용은 논문 원본을 참고하길 바란다.

1. Holtkamp DJ, Kliebenstein JB, Neumann EJ, Zimmerman JJ, Rotto HF, Yoder TK, et al. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on United States pork producers. J. Swine Heal Prod. 2013; 21(2):72–84.

2. Duan X, Nauwynck HJ, Pensaert MB. Effects of origin and state of differentiation and activation of monocytes/macrophages on their susceptibility to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Arch. Virol. 1997; 142(12):2483–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007050050256 PMID: 9672608

3. Duan X, Nauwynck HJ, Pensaert MB. Virus quantification and identification of cellular targets in the lungs and lymphoid tissues of pigs at different time intervals after inoculation with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Vet. Microbiol. 1997; 56(1–2):9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(96)01347-8 PMID: 9228678

4. Beyer J, Fichtner D, Schirrmeier H, Polster U, Weiland E, Wege H. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV): Kinetics of infection in lymphatic organs and lung. J. Vet. Med. B. Infect. Dis.Vet. Public Health. 2000; 47(1):9–25. PMID: 10780169

5. Thanawongnuwech R, Halbur PG, Thacker EL. The role of pulmonary intravascular macrophages in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2000; 1(2):95–102. PMID: 11708601

6. Lelkes E, Headley MB, Thornton EE., Looney MR, Krummel MF. The spatiotemporal cellular dynamics of lung immunity. Trends Immunol. 2014; 35(8):379–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2014.05.005 PMID: 24974157

7. Oleksiewicz MB, Nielsen J. Effect of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) on alveolar lung macrophage survival and function. Vet Microbiol. 1999; 66(1):15–27. PMID: 10223319

8. Drew TW. A review of evidence for immunosuppression due to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet. Res. 2000; 31(1):27–39. https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2000106 PMID: 10726636

9. Opriessnig T, Gime´nez-Lirola LG, Halbur PG. Polymicrobial respiratory disease in pigs. Anim. Heal Res. Rev. 2011; 12(2):133–48. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1466252311000120 PMID: 22152290

10. Go´mez-Laguna J, Salguero FJ, Pallare´s FJ, Carrasco L. Immunopathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in the respiratory tract of pigs. Vet. J. 2013; 195(2):148–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.11.012 PMID: 23265866

11. De Baere MI, Van Gorp H, Delputte PL, Nauwynck HJ. Interaction of the European genotype porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) with sialoadhesin (CD169/Siglec-1) inhibits alveolar macrophage phagocytosis. Vet. Res. 2012; 43(1):47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1297-9716-43-47 PMID: 22630829

12. Van Reeth K, Nauwynck H, Pensaert M. Dual infections of feeder pigs with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus followed by porcine respiratory coronavirus or swine influenza virus: A clinical and virological study. Vet. Microbiol. 1996; 48(3–4):325–35. PMID: 9054128

13. Thacker EL, Halbur PG, Ross RF, Thanawongnuwech R, Thacker BJ. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae potentiation of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus-induced pneumonia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999; 37(3):620–7. PMID: 9986823

14. Thanawongnuwech R, Brown GB, Halbur PG, Roth JA, Royer RL, Thacker BJ. Pathogenesis of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus-induced Increase in Susceptibility to Streptococcus suis Infection. Vet. Pathol. 2000; 37(2):143–52. https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.37-2-143 PMID: 10714643

15. Brockmeier SL, Palmer M V, Bolin SR, Rimler RB. Effects of intranasal inoculation with Bordetella bronchiseptica, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, or a combination of both organisms on subsequent infection with Pasteurella multocida in pigs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2001; 62(4):521–5. PMID: 11327458

16. Yu J, Wu J, Zhang Y, Guo L, Cong X, Du Y, et al. Concurrent highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection accelerates Haemophilus parasuis infection in conventional pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2012; 158(3–4):316–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.03.001 PMID: 22460022

17. Chin AC, Morck DW, Merrill JK, Ceri H, Olson ME, Read RR, et al. Anti-inflammatory benefits of tilmicosin in calves with Pasteurella haemolytica-infected lungs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1998; 59(6):765–71. PMID: 9622749

18. Jaff A, Bush A. Anti-inflammatory effects of macrolides in lung disease. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2001; 31 (6):464–73. PMID: 11389580

19. Buret AG. Immuno-modulation and anti-inflammatory benefits of antibiotics: The example of tilmicosin. Vol. 74, Can. J. Vet. Res. 2010; 74(1): 1–10. PMID: 20357951

20. Kanoh S, Rubin BK. Mechanisms of action and clinical application of macrolides as immunomodulatory medications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010; Jul; 23(3):590–615. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00078-09 PMID: 20610825

21. Fischer CD, Beatty JK, Stephanie C, Morck DW, Lucas MJ, Buret AG. Direct and Indirect Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Tulathromycin in Bovine Macrophages: Inhibition of CXCL-8 Secretion, Induction of Apoptosis, and Promotion of Efferocytosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013; 57(3):1385–93. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01598-12 PMID: 23295921

22. Moges R, De Lamache DD, Sajedy S, Renaux BS, Hollenberg MD, Muench G, et al. Anti-Inflammatory Benefits of Antibiotics: Tylvalosin Induces Apoptosis of Porcine Neutrophils and Macrophages, Promotes Efferocytosis, and Inhibits Pro-Inflammatory CXCL-8, IL1α, and LTB4 Production, While Inducing the Release of Pro-Resolving Lipoxin A4 and Resolvin D1.Front. Vet. Sci. 2018; 5:57. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2018.00057 PMID: 29696149

23. Pol JMA, Van Leengoed LAMG, Stockhofe N, Kok G, Wensvoort G. Dual infections of PRRSV/influenza or PRRSV/Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae in the respiratory tract. Vet. Microbiol. 1997; 55(1–4):259–64. PMID: 9220621

24. Chiers K, De Waele T, Pasmans F, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F. Virulence factors of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae involved in colonization, persistence and induction of lesions in its porcine host. Vet. Res. 2010: 41(5): 65.

25. Duquette SC, Fischer CD, Williams AC, Sajedy S, Feener TD, Bhargava A, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of tulathromycin on apoptosis, efferocytosis, and proinflammatory leukotriene B4 production in leukocytes from actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae–or zymosan-challenged pigs. Am J Vet Res. 2015; 76(6):507–19. https://doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.76.6.507 PMID: 26000598

26. Hunter CA, Jones SA. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nature Immunology. Nat. Immunol. 2015; 16(5):448–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3153 PMID: 25898198

27. Sassu EL, Fro¨mbling J, Duvigneau JC, Miller I, Mu¨llebner A, Gutie´rrez AM., et al. Host-pathogen interplay at primary infection sites in pigs challenged with Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. BMC Vet. Res. 2016; 13(1):64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-0979-6 PMID: 28245826

28. Fischer CD, Beatty JK, Zvaigzne CG, Morck DW, Lucas MJ, Buret AG. Anti-Inflammatory Benefits of Antibiotic-Induced Neutrophil Apoptosis: Tulathromycin Induces Caspase-3-Dependent Neutrophil Programmed Cell Death and Inhibits NF- κB Signaling and CXCL8 Transcription. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011; 55(1):338–48. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01052-10 PMID: 20956586

29. Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-β, PGE2, and PAF. J. Clin. Invest. 1998; 101(4):890–8. https://doi.org/10. 1172/JCI1112 PMID: 9466984

30. Fullerton JN, Gilroy DW. Resolution of inflammation: A new therapeutic frontier. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015; 15(8):551–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2016.39 PMID: 27020098